News vouchers are an effective way to restore diverse, vibrant local journalism

What Seattle's Democracy Vouchers program can teach us about the public funding of news

American journalism is in crisis. The number of newsroom jobs is at its lowest level in decades. Many local newspapers have closed entirely, and others have been purchased by investment firms who have reduced staff to extract profit from the remaining brand equity of the news outlets. This decline of US journalism means that citizens are losing access to the critical information they need to participate in democracy.

An exciting new bill to rebuild local news, the Local Journalism Sustainability Act (LJSA), has recently been reintroduced in Congress by a bipartisan pair of House members: Reps. Dan Newhouse (R-WA) and Ann Kirkpatrick (D-AZ). One provision of this bill is an individual tax credit, designed to reimburse citizens for subscriptions to local news outlets.

At DPN, we provide information to state government leaders on forward-thinking policies they can implement to deepen democracy. We agree that public funding for news is essential and should be a high priority for us all. While individual tax credits will have a positive effect, we believe that a powerful way to restore and rebuild local news is via news vouchers, which allow citizens to directly fund news outlets of their choice by assigning vouchers to outlets, which redeem those vouchers for public funds.

Public news funding is essential to achieve the level of journalism needed to sustain democracy, as news is a public good. For much of the 19th century, newspapers had a monopoly on local classified advertising, which allowed a vigorous journalism industry. The internet broke that monopoly, and exposed the weakness of advertising-reliant journalism. A further blow was struck to the relationship between news outlet audience and advertisers by the digital advertising duopoly of Facebook and Google, which have demolished the traditional ability of news outlets to control the ads marketed to their readership.

The massive decline of advertising profits in recent years has led not just to the closing of many outlets, but has created incentives for remaining outlets to shift away from reporting and investigative journalism to more profitable content: entertainment and outrage. Other democratic countries publicly fund journalism, and historically the United States has publicly funded journalism. Our current over-reliance on market forces to support U.S. journalism is what is unique, and which public news funding models seek to repair.

At the federal level, passing the federal LJSA would be a tremendous step forward to repair local news and improve American journalism. But this would be just a start. Ideally the individual tax credit system in that bill would be built upon, and expanded, by a federal voucher system in the near future. Meanwhile, state governments should themselves look to rebuild more vibrant local news by implementing voucher systems.

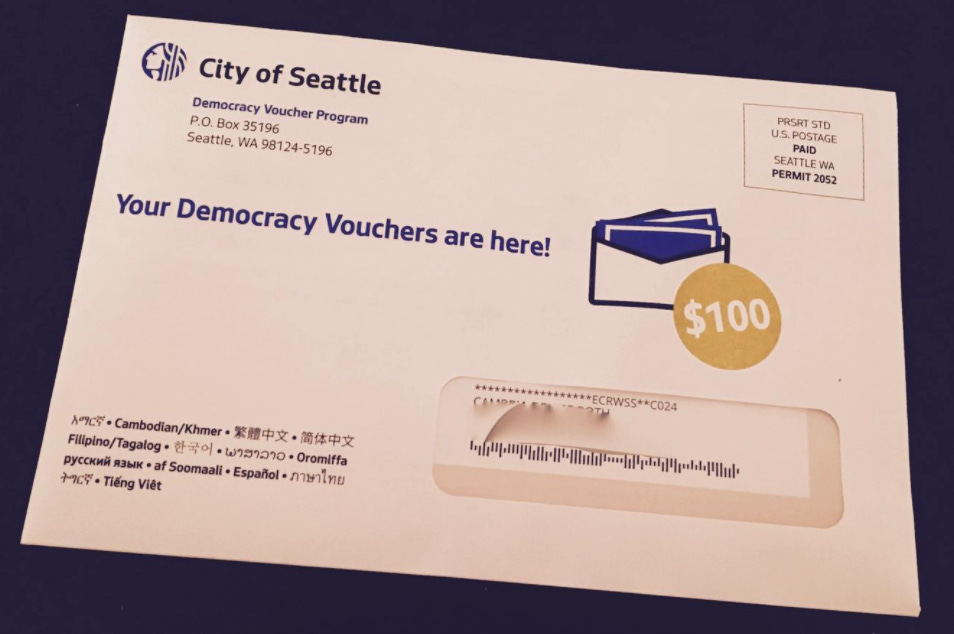

Here, we explain why a news voucher system is superior to an individual tax credit for funding local news. There is recent experience in public campaign finance that is informative: Seattle implemented a voucher system to fund campaigns in 2017. These vouchers have been practical and effective. Today, public vouchers for news can be provided and redeemed easily — via a website or as a physical piece of paper — and Seattle’s experience shows that both systems are effective. Vouchers are content-neutral, as citizens (not governments) decide where to allocate them. And caps and transparency rules can be used to make sure that both large outlets and a diversity of smaller news outlets benefit from a voucher public funding system.

We see three major reasons to prefer vouchers over tax credits:

Participation rates: More people are likely to use vouchers than they are to use a tax credit. Public campaign finance systems provide instructive precedents. Seattle implemented a voucher system to fund campaigns in 2017, and found that vouchers have been enthusiastically embraced and dramatically increase citizen involvement. In contrast, tax credits for campaign donations have also been implemented — in the past at the federal level, and currently in several states — and these systems have had low rates of participation.

Diversity of outlets and diversity of the subscriber pool: Another goal of a news funding system is to increase diversity of news outlets and also promote new, startup news outlets. Vouchers require no up-front cash outlay, and so vouchers are painless to use for all types of citizens, including those living paycheck-to-paycheck. Currently, American news caters to a small part of the population, mainly the highly educated and wealthy, and there are large differences in news awareness across socioeconomic groups. Because vouchers will reach a larger part of the public than a tax credit, vouchers are likely to boost outlets that provide news for currently news-underserved communities, and therefore inform a larger fraction of the public about events that impact their lives.

Citizen engagement: Finally, vouchers should strengthen bonds between citizens and the outlets that they use vouchers to fund. First, vouchers are concrete. While tax credits require completing a form at tax filing time, the action of redeeming a voucher is similar to the experience of buying something with cash. Citizens receive a voucher, actively choose where to spend it, and will often receive immediate benefits, such as a subscription, in return. Second, news outlets will be incentivized to pursue citizens to grant them their vouchers. In Seattle, this has occurred, as campaigns actively solicit vouchers from individual donors. Building a loyal subscriber base — that is, increasing engagement between consumers of news and the outlets they rely on for news — is a productive business model for modern journalism, and vouchers seem likely to help build such loyal subscriber bases.

Lessons from public campaign finance: vouchers are widely used — and tax credits are not

The example of public campaign finance shows the difference in outcomes between voucher and tax credit systems.

A voucher system to fund candidates was implemented in Seattle beginning with the 2017 municipal elections. In this “democracy voucher” system, residents are issued public funds in the form of vouchers for every election, which they can donate to political candidates.

Seattle’s participation rates are high and growing, as Tom Latkowski summarizes in DPN’s Democracy Vouchers policy kit:

The program was first administered for the 2017 election. 80,000 vouchers were returned [by 540,000 eligible citizens]. Across three eligible races, 17 candidates pledged to participate, including five of six general election candidates and all winners.

In 2019, the program was administered for seven city council races. 35 candidates qualified for the program, including six of seven general election winners. In total, 147,128 vouchers [from 450,293 citizens] were returned, nearly doubling the 2017 rate.

Surveys show a “high level of public awareness,” with only 37% of residents reporting that they have never heard of the program in March of 2018. Awareness is especially high among people of color, with only 25% of those surveyed having not heard of the program.

In 2021, Seattle’s democracy voucher system will for the first time expand to the mayoral race, and the vouchers are expected to increase participation in the mayoral election as they have done for the city council elections.

In contrast to the success of Seattle’s vouchers, there have been several campaign donation tax credit systems aiming to fund campaigns, and participation in these systems have been low. A 2017 Brennan Center report reviews the somewhat bleak history. There was a federal individual tax credit for political campaign donations that began in 1972 and ended in 1986. Participation was between 1.4-2.8% for the first five years of the program, and never reached higher than 5.8%.

Tax credits at the state level have even worse participation. Six states have political donation tax credits. While these credits have been shown to have some effect on expanding the number of people who donate to campaigns, the effects are small. According to the Brennan Center report, "Participation in these programs is low, often less than two percent." While there are ways participation in a tax credit system could be improved—for example, by funding outreach programs designed to increase participation—a bigger problem seems difficult or impossible to fix with tax credits: that it is the wealthy, white-collar, and highly-educated are who are most likely to take advantage of a tax credit.

Diversity of outlets: Current news largely caters to the well-connected, and vouchers would reach a wider population

The current American journalism system serves the educated and well-connected. In large part, this is because America has had, for decades, a journalism industry highly dependent on advertising. This advertising dependence, which existed long before the rise of the Internet, incentivizes news outlets to serve profitable demographics, leading to coverage weighted towards the interests of wealthier citizens with disposable income.

American journalism’s prioritization of wealthy demographics (the “rich, white, and blue”, as styled by a recent book on the state of journalism) also parallels the fact that large parts of the American electorate being under-informed about news. As of 2008, US citizens with a high school degree or less were two to three times less knowledgeable about political events than citizens of similar education levels in Denmark, Finland, or the UK (each of which publicly subsidizes journalism at a much higher level than the US.) And a recent working paper from economists Andrea Prat and Charles Angelucci shows that a similar disparity in news knowledge exists in the US across socioeconomic lines.

Therefore, for a local news subsidy program to rebuild American public debate, it should aim to increase diversity of news outlets. The US needs more outlets that supply news for the working class and for historically-excluded groups.

A voucher system is likely to be more effective than a tax credit at reaching a diverse array of citizens. First, taking a tax credit requires both an initial cash outlay and follow-up paperwork at tax filing time, which suggests that tax credits will tend to favor those with disposable income and those who are used to spending time and effort on paperwork tasks. Because vouchers are cash equivalents that can be directly and immediately spent — whether via a website or through transfer of a physical voucher, both of which are used in Seattle — they should be more easily used by more diverse groups of citizens. Indeed, Seattle’s voucher system increased the political donor pool’s diversity. In contrast, federal tax credits for education, which might be thought to incentivize citizens to pursue higher education, have instead had “zero effect on college attendance.” This is presumably because the credits act only to compensate those who are already pursuing education, rather than act to expand the pool of citizens that might attend college.

Citizen engagement: Vouchers give citizens a tangible item to assign, and news outlets would be incentivized to solicit vouchers

Seattle’s voucher system began with paper vouchers and now also uses a website to assign vouchers. This means that to use their vouchers, Seattle citizens take tangible actions that have immediate feedback for them. They receive the vouchers, they choose the news outlet, they assign the voucher, and they receive the benefits. No cash outlay is needed and no tax return paperwork must be tracked and completed. This ease of use, beyond just increasing the number and diversity of citizens involved, also seems likely to be contributing to the expansion of the donor pool seen in Seattle’s system.

Another way vouchers would increase citizen engagement with news outlets is by incentivizing outlets to solicit vouchers. In Seattle, candidates now canvass citizens to ask for their vouchers, and in a news voucher system, news outlets would likely advertise to citizens to ask for their vouchers. And vouchers seem likely to incentivize new startup news outlets, as entrepreneurial founders find startup “capital” by assembling a group of citizens to give the new outlet their vouchers. Because vouchers are likely to be used by more citizens — and a more diverse array of citizens — than tax credits, the news startups created by a voucher system will also be more diverse and should serve new audiences of citizens that were not previously news subscribers.

In principle, outlets could also solicit subscriptions by advertising tax credit incentives. However, in practice such solicitation appears not to be widespread for public campaign finance tax credits. The low levels of participation in state tax credit systems suggest few candidates in Virginia, or Minnesota, for example, are successful at marketing a tax credit incentive to potential individual donors.

Voucher programs are practical and scalable

A voucher system that boosts news outlets seems likely to develop its own momentum. Citizens will want to keep the value they get from subscribing to news via a voucher, building a political base for news vouchers and for robust journalism. And news outlets themselves will have an incentive to argue to sustain the voucher system. Again, Seattle’s experience is informative: The democracy voucher system has shown an increase in participation and approval over time.

An advantage of the current LJSA federal tax credit proposal is that it is structured as mandatory spending (entitlement spending), so it will not be subject to the annual appropriations process, and is less likely to become the subject of yearly partisan budget battles. Voucher programs could be structured in this way as well. However, because voucher programs are likely to generate increased support over time, using discretionary spending for a voucher program should still lead to a functional system.

The main potential risks in a voucher system seem similar to risks that would arise in a tax credit system. For example, a voucher system might create increased polarization as citizens seek and fund news that supports their existing views. Yet any effect on polarization would seem to be stronger in a tax credit system, which is likely to engage a smaller group of citizens, and a group that is more elite, than vouchers. Also, if incentives from education tax credits are a guide, the group that takes a tax credit will be composed largely of existing subscribers to news outlets. One reason for polarization today is the shift towards social media that merely aggregates a smaller and smaller stream of original information as journalism declines. With more original news generated by a public subsidy, more news outlets should differentiate their content from the few large national outlets, leading to a more diverse news ecosystem. Consumption of diverse news has been shown to decrease polarization.

A second force driving decreased polarization from a public subsidy would be the increased bond between citizens and the news outlets they fund. Outlets that rely on a loyal subscriber base will have less incentive to chase virality and clicks, a motivation that has been a driver of polarization in America.

The example of Seattle shows that voucher systems can work today to allow citizens to allocate public money in content-neutral ways. Vouchers can be allocated through websites that scale up to the entire population, and rules on public disclosure can reduce the risk of co-option or capture. Now is a good time to advocate for creating news voucher systems for funding local journalism to revitalize American democracy.

Mark Histed is the policy organizer working on DPN’s Citizen News Vouchers project. He has expertise with government grants, procurement, and contracting as both the recipient of scientific grants and in work for the federal government. He is a neuroscientist with interests in how information flows through networks and is used to make decisions. Mark has been interested in local news since he was a middle schooler delivering the Scranton Times (now the Times-Tribune, following a consolidation.) Contact Mark at: MarkHisted@DemocracyPolicy.network.